This is just a collection of some the artwork, geometry, instruments, and designs of the ancient world.

The Assumption of the Virgin, 1475–1476, is a large (228.6 x 377.2 cm) painting in tempera on wood panel by Francesco Botticini. It portrays Mary’s assumption and was commissioned as the altarpiece for a church in Florence and is now in the National Gallery, London.

Raphael’s depiction of the unmoved mover from the Stanza della Segnatura:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unmoved_mover

Nicolas Vleughels (1668 Paris – 1737 Rom): Shield of Achilles according to the description in the Homeric Iliad, 18th century, Copper engraving

The Divine Comedy’s Empyrean, illustrated by Gustave Doré

The Candida Rosa is the place where the souls reside in the Paradise built by Dante :

«Therefore in the form of a white rose / the holy militia was shown to me / which Christ made a bride in his blood.»

(Paradiso – Canto thirty-first , vv. 1-3 )

In ancient European cosmologies inspired by Aristotle, the Empyrean Heaven, Empyreal or simply the Empyrean, was the place in the highest heaven, which was supposed to be occupied by the element of fire (or aether in Aristotle’s natural philosophy). The word derives from the Medieval Latin empyreus, an adaptation of the Ancient Greek empyros (ἔμπυρος), meaning “in or on the fire (pyr)”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empyrean

A page from Oresme’s Livre du ciel et du monde, 1377, showing the celestial spheres.

In his Livre du ciel et du monde Oresme discussed a range of evidence for and against the daily rotation of the Earth on its axis.[11] From astronomical considerations, he maintained that if the Earth were moving and not the celestial spheres, all the movements that we see in the heavens that are computed by the astronomers would appear exactly the same as if the spheres were rotating around the Earth. He rejected the physical argument that if the Earth were moving the air would be left behind causing a great wind from east to west. In his view the Earth, Water, and Air would all share the same motion.[12] As to the scriptural passage that speaks of the motion of the Sun, he concludes that “this passage conforms to the customary usage of popular speech” and is not to be taken literally.[13] He also noted that it would be more economical for the small Earth to rotate on its axis than the immense sphere of the stars.[14] Nonetheless, he concluded that none of these arguments were conclusive and “everyone maintains, and I think myself, that the heavens do move and not the Earth.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicole_Oresme

La materia della Divina commedia di Dante Alighieri, Plate VI: “The Ordering of Paradise” by Michelangelo Caetani (1804–1882)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_heavens

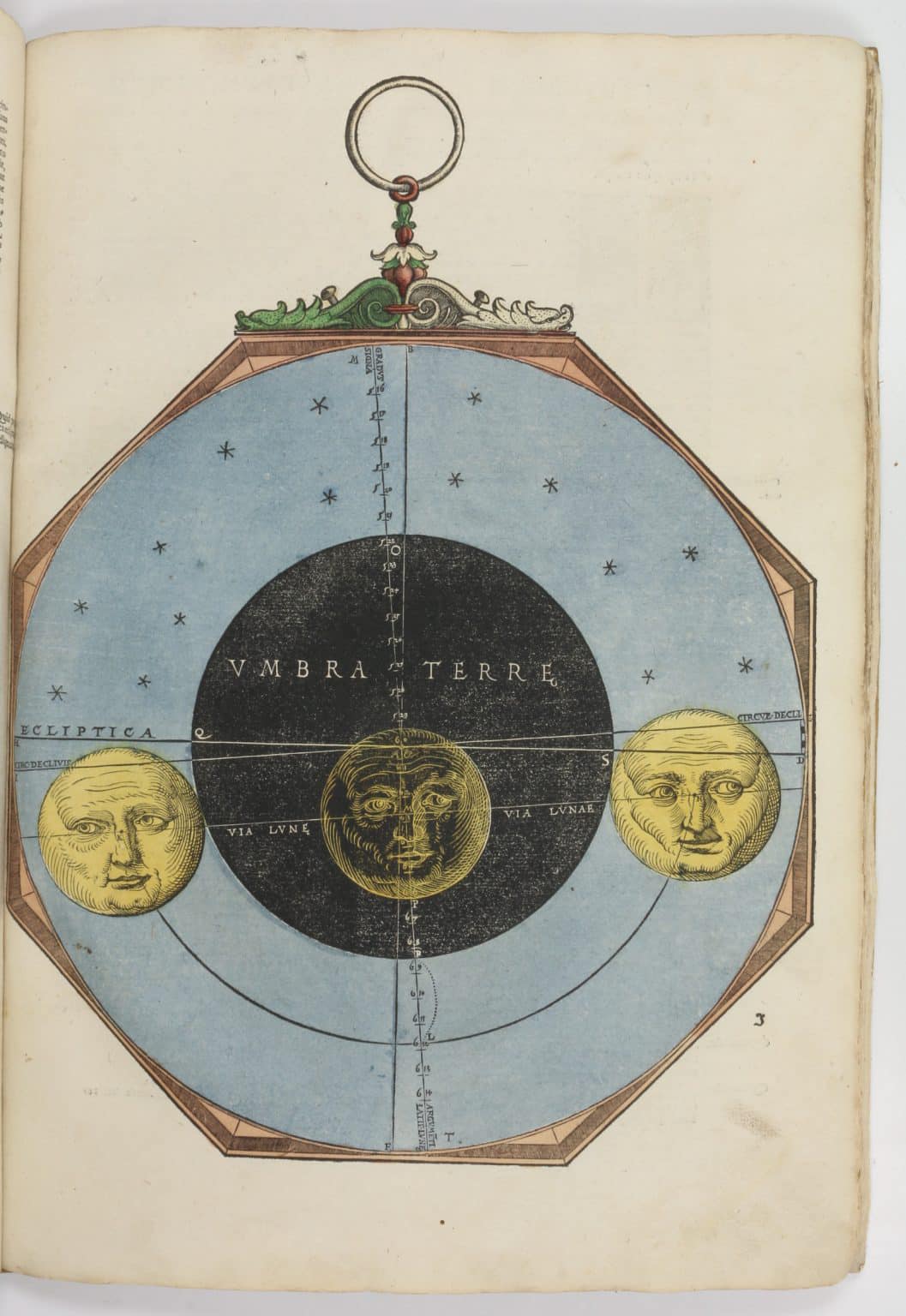

Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (“The Great Art of Light and Shadow”) is a 1646 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher

“Whether you consider Father Athanasius Kircher (1601-1680) to be the embodiment of polymathic inquisitiveness or an overrated plagiarist who contributed nothing but ‘chaff’ to the intellectual life of the 17th century, the abundance of illustrations throughout his works remain enigmatic curiosities nevertheless.

‘An ecstatic journey through which the world works’ by Athanasius Kircher

It is the only work by Kircher devoted entirely to astronomy, and one of only two pieces of imaginative fiction by him. A revised and expanded second edition, entitled Iter Exstaticum, was published in 1660.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Itinerarium_exstaticumIn 1660, Kircher published

Itinerarium exstaticum coeleste (‘Ecstatic Celestial Journey’), which was based on a dream he had in which he traveled from the earth to outer space (space was a fluid, rather than a solid). This work dispelled almost all of the Aristotelian ideas about cosmology. In it, the angel Cosmiel reveals all the secrets of heaven and earth to Kircher, as the character “Theodidactus” (“taught by God”).

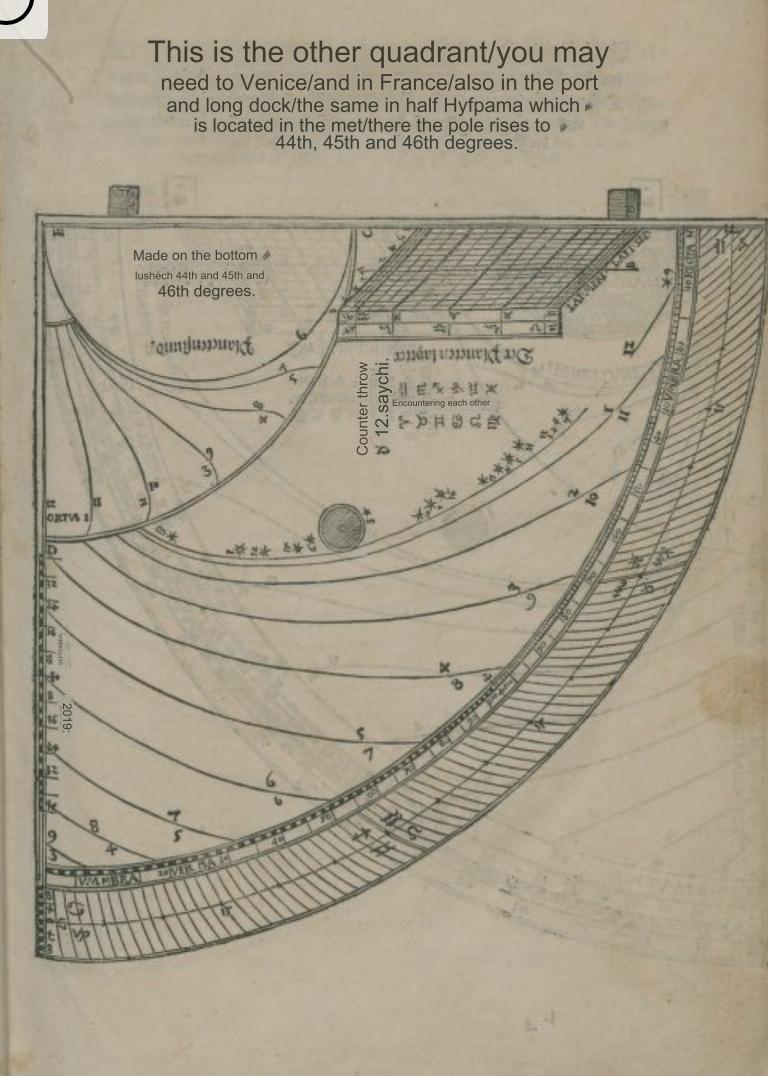

ASTRONOMICS AND THE EARLY RECENT DISCOVERY AND THE FIRST

EDITION OF THE NIVNG,

Adjoined to this are also other formidable instruments, adapted to the different hours of the night and the day, those from the Sun, the!Moon sand the Stellifo, both erratic andfixed, to the knowledge of which, on this side, all the work of the Preceptor may easily arrivo.

Then there are the dimensions of the height, depth, and depth of the Wells, Towers,….

translated German and Latin in this book

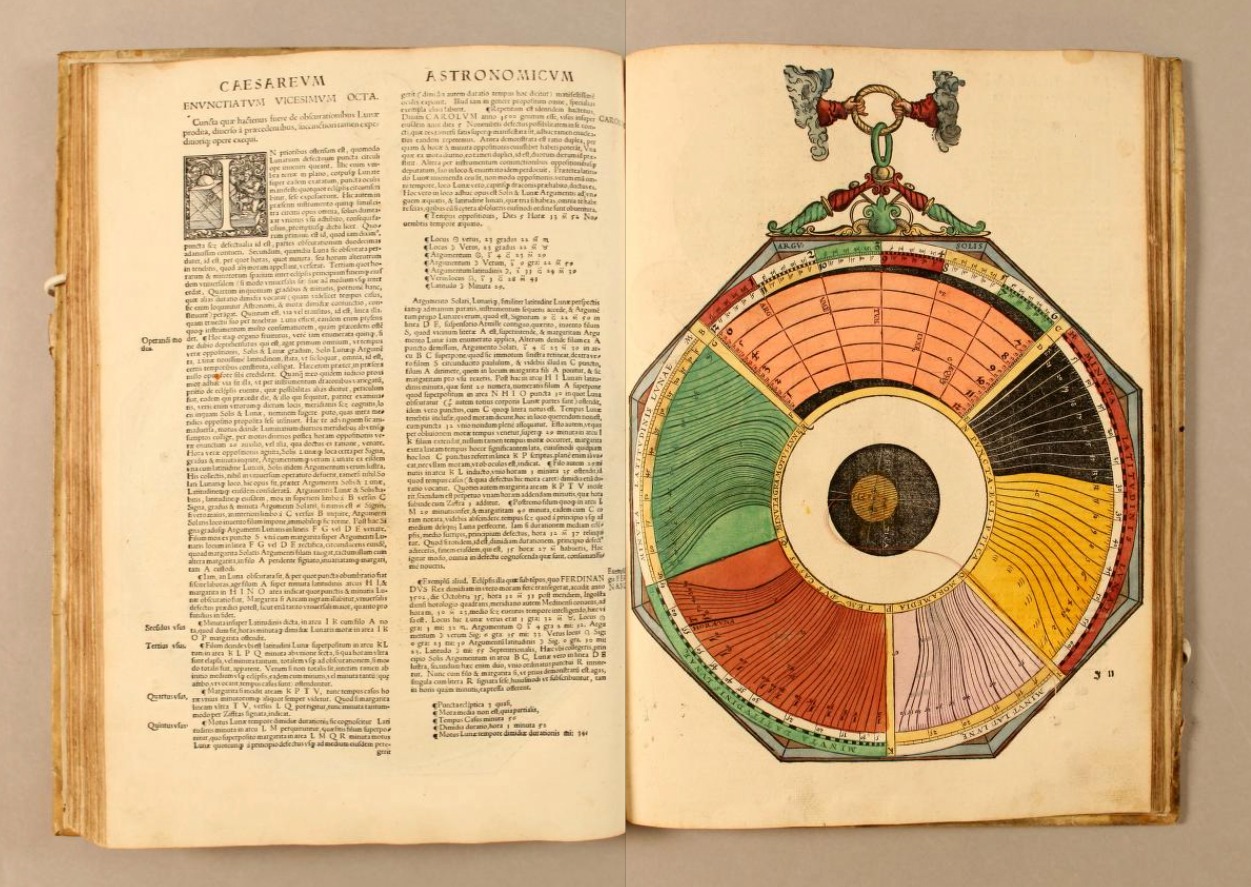

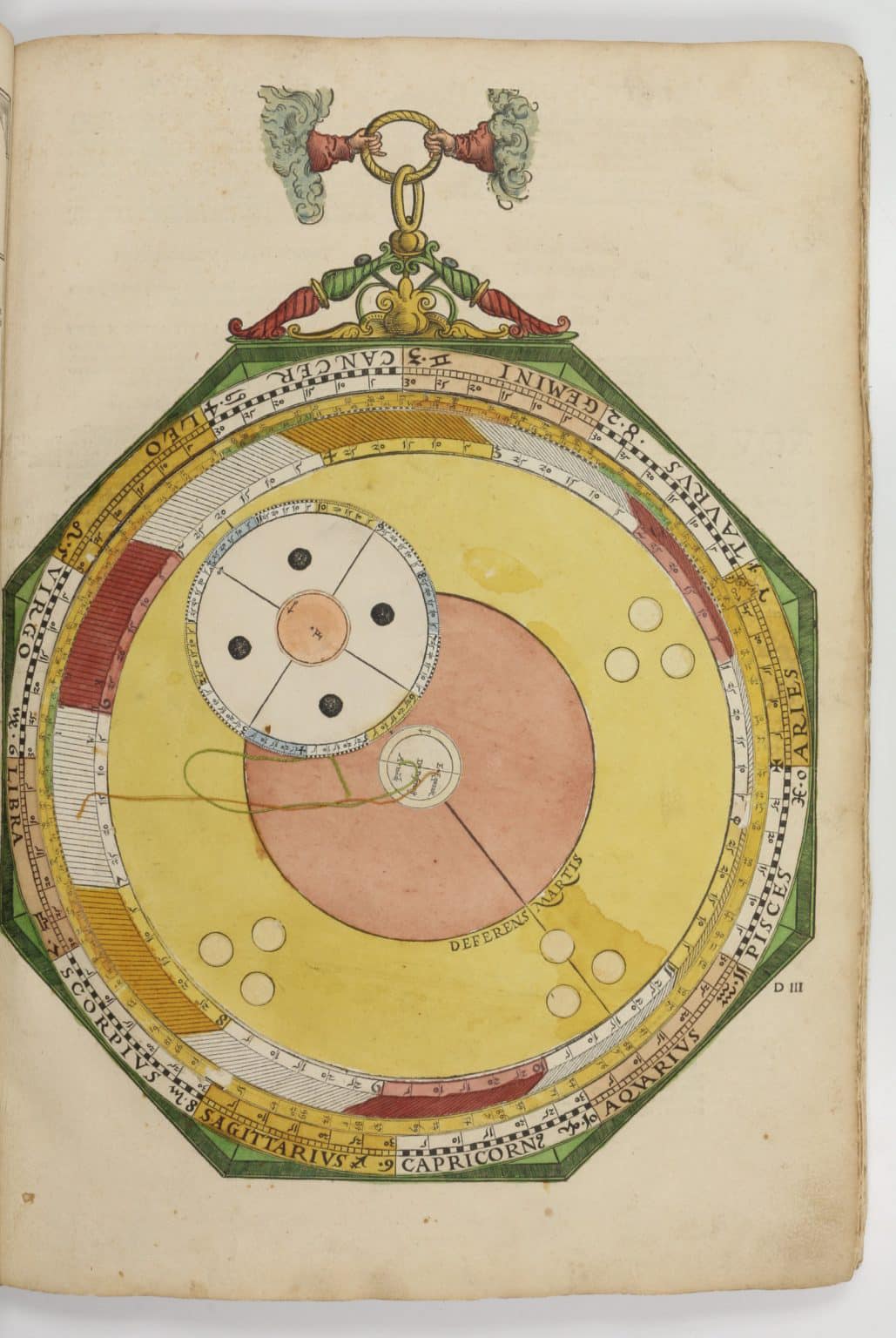

Astronomicum cæsareum

by Apian, Peter, 1495-1552

German humanist, known for his works in mathematics, astronomy and cartography.[2] His work on “cosmography”, the field that dealt with the earth and its position in the universe, was presented in his most famous publications, Astronomicum Caesareum (1540) and Cosmographicus liber (1524). His books were extremely influential in his time, with the numerous editions in multiple languages being published until 1609.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petrus_Apianus“Hipparchus (c.190-c.120 BC), Ancient Greek astronomer, at the Alexandria Observatory, Egypt. At left is the armillary sphere he invented. (at right is the celestial globe) Hipparchus is considered one of the greatest astronomers of antiquity. He calculated the length of the year and discovered the precession of the equinoxes. It is thought that the later work of Ptolemy was based on the work done by Hipparchus.”

The or turquet is a medieval astronomical instrument designed by persons unknown to take and convert measurements made in three sets of coordinates: horizon, equatorial, and ecliptic. It is characterised by R. P. Lorch as a combination of Ptolemy’s astrolabon (Greek: aστpoλaẞov) and the plane astrolabe.[1] In a sense, the torquetum is an analog computer.

The origins of the torquetum are unclear. Its invention has been credited to multiple figures, including Jabir ibn Aflah, Bernard of Verdun and Franco of Poland.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TorquetumAstrolabes

The Astrolabe is an astronomical instrument used from around the 6th century to measure time and position by determining the altitude of heavenly bodies like the Sun and certain stars. Measurements were taken in reference to the viewer’s horizon and the meridian and using a representation or map of the sky with a measuring scale engraved on the instrument itself.

Purpose of the Astrolabe: The device known specifically as a planispheric astrolabe was used to measure the positions of the stars, Sun, and planets in the sky so that by finding one fixed point the user could then turn the dial of the astrolabe and have an accurate (if two-dimensional) view of the whole celestial hemisphere. It could also be used to determine the height of mountains, calculate time, or as a map to find a specified place.

Size

Astrolabes were usually made of metal and were smaller than 50 cm (19.5 in) so that they could easily be held in one hand and carried anywhere. Brass is the most common material used, but some surviving examples are made of copper or iron. Finer pieces often have gold or silver inlay and almost all are circular.

Operation

The astrolabe is first suspended from the thumb using a ring and the viewer looks along a moveable sighting arm (the alidade) or through two aligned loops at the object desired such as a specific star. If measuring the angle of the Sun, then one looked at the beam of sunlight cast on the instrument after it passed through the loops. The altitude is then determined by referencing a measuring scale engraved on one side of the instrument. On the other side of the astrolabe is a map of the skies of the northern hemisphere. The stars are represented by a network or open pattern of pointers

History

From the astrolabe, other instruments evolved such as the astrolabe-quadrant which was specifically designed to measure time and dates. The telescope, invented around 1608 in the Netherlands, revolutionised the observation of the skies and soon telescopic sights were being fitted to fixed observational instruments which could give much more accurate readings.

–

**Astrolabe Usage**: Used from the 6th century to measure time and celestial positions by determining the altitude of stars and the Sun.

–

**Ancient Origins**: Likely evolved from Mediterranean sundials and may have been invented by Hipparchus in the 2nd century BCE.

–

**Cultural Spread**: Astrolabes were widely adopted in the Arab world, Europe, and India, with knowledge transferring via Islamic Spain by 1000 CE.

–

**Functionality**: The astrolabe could determine time, celestial positions, latitude, and geographical features, serving as a crucial tool for both astronomers and navigators.

–

**Marine Astrolabe**: Adapted for sea navigation, it helped sailors like Columbus and Vespucci calculate their latitude.

–

**Influence on Instruments**: The astrolabe influenced the creation of the sextant and telescope, continuing to shape scientific tools until the GPS era.

–

**Notable Descriptions**: Geoffrey Chaucer and Johannes Stoeffler provided famous instructional guides on how to use the astrolabe.

–

**Design & Materials**: Usually made of brass, astrolabes were compact, ornate, and sometimes equipped with extras like a magnetic compass.

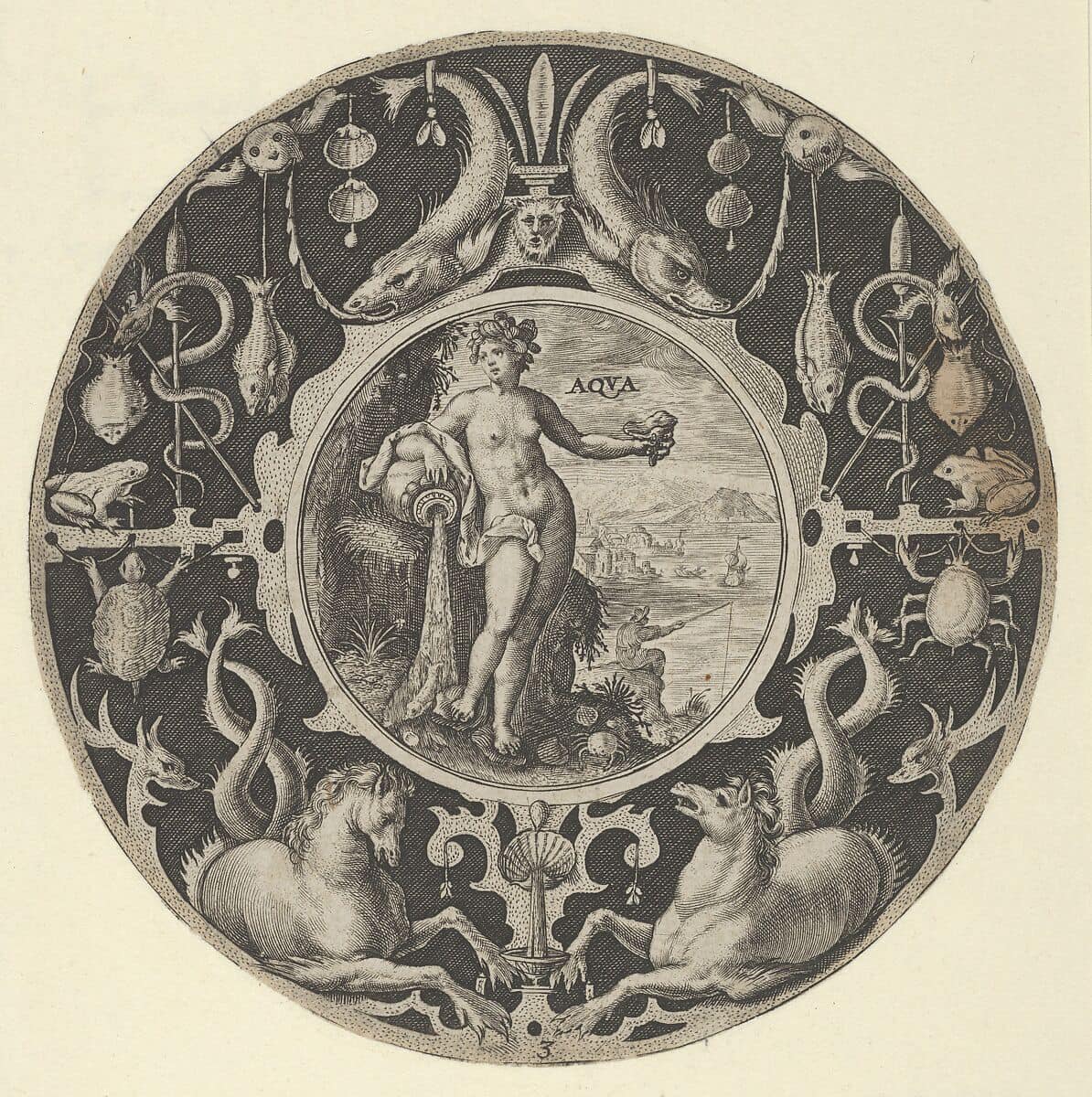

Crispijn de Passe the Elder (Netherlandish, Arnemuiden 1564–1637 Utrecht)

‘Aqua’ in a Decorative Border with Sea Creatures, from a Series of Circular Designs with the Four Elements, 1590–1612 Netherlandish

Title: ‘Aqua’ in a Decorative Border with Sea Creatures, from a Series of Circular Designs with the Four Elements,

Artist: Crispijn de Passe the Elder (Netherlandish, Arnemuiden 1564–1637 Utrecht), Date: 1590–1612

Medium: Engraving,Dimensions: Sheet: 5 × 4 3/4 in. (12.7 × 12.1 cm)

Design for a circular plate with the element of Water personified as a standing female figure holding a shell in her left and and leaning on an over turned vessel, which issues a stream of water and fish. This scene is shown in a medallion at center and is surrounded by a broad band with various aquatic animals and sea monsters, including two horses with fish’s tails below. Plate 3 from a series of four devoted to the Four Elements

The upside-down world, Crispijn van de Passe, 1574 – 1637, Allegory of the upside-down world with Democritus and Heraclitus

(the laughing and the weeping philosopher). Heraclitus has his eyes sadly lowered while the smiling Democritus points to a globe. On the globe, the folly of mankind is represented by jesters who amuse themselves with fighting, playing, and making love. In the background a funeral procession and a raging sea with a sinking ship.

On the globe sit the devil, Foolishness personified by a jester, and the female personification of Lust (Luxuria). In the upper corners angels with vanitas symbols. In the margin a twelve-line poem, in three columns, in German, and an eight-line poem, in two columns, in French., print maker: Crispijn van de Passe (I), Crispijn van de Passe (I), (mentioned on object), publisher: Crispijn van de Passe (I), (mentioned on object), unknown, 1574 – 1637, paper, etching, h 238 mm × w 269 mm

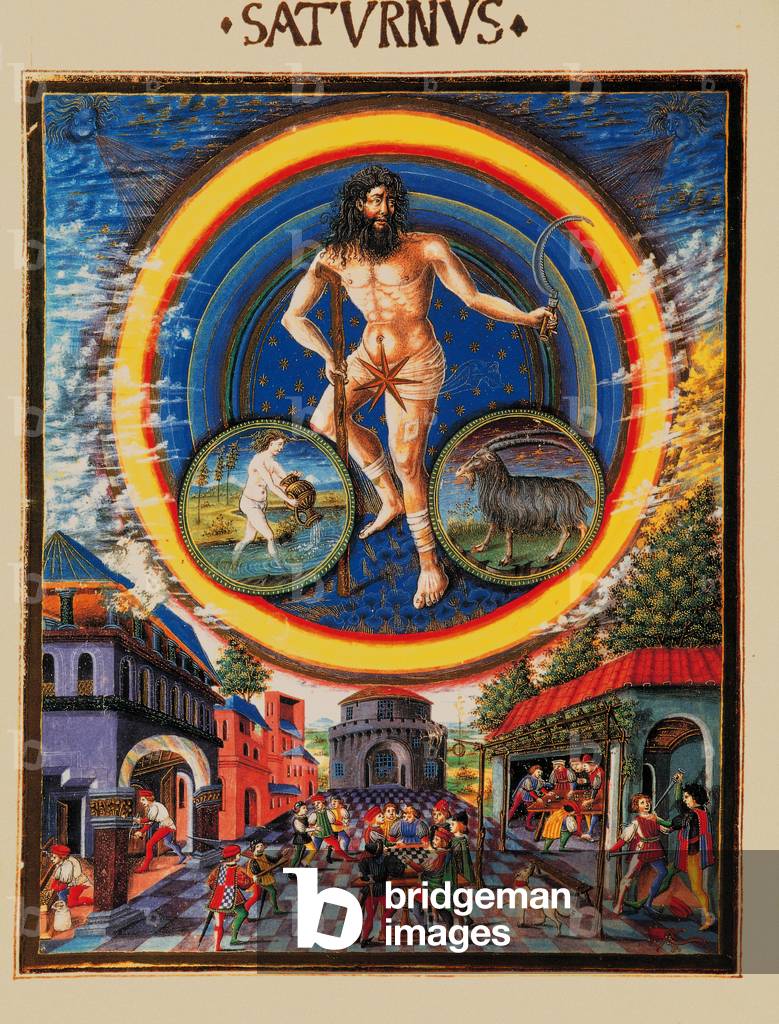

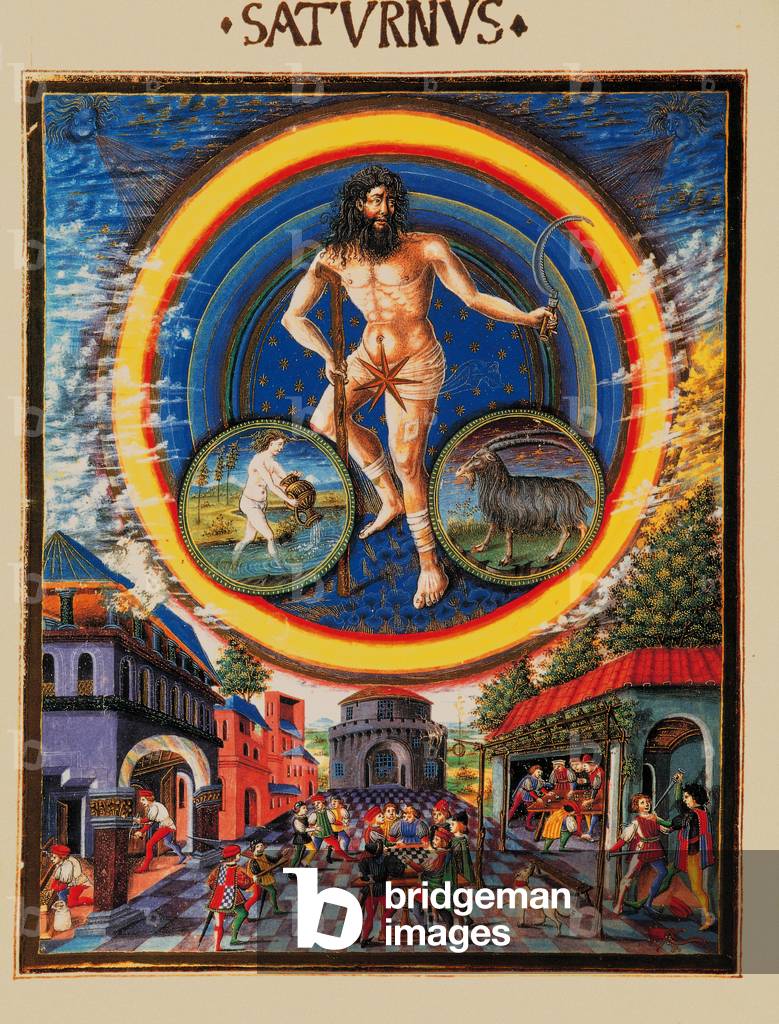

De Sphaera Mundi

Saturn, 1470 – 1480 (parchment manuscript)

The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise by Giovanni di Paolo in 1445

(originally part of the altarpiece in Siena’s church of San Domenico). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meta-historical_fall

Yakkha upholding the Dhammacakka

Yakkha upholding the Dhammacakka, Wat Sri Suphan, Chiang Mai

Peaceful and Wrathful Deities of the Bardo – 18th Century – Tibet – pigments on cloth

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Discover more from JoeDubs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.