Many of the geniuses throughout history understood that earth is hollow and literally contains the entire universe as we know it. They knew this information would never become overtly available to the public so they encoded it into their poetry and artwork.

“Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.” – Albert Camus

“The exact contrary of what is generally believed is often the truth.” – Jean de la Bruyère

William Blake

William Blake (1757-1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker known for his romantic poetry that merged myth, religion and the human condition. Influenced by

spiritual visions and a rejection of materialism, his poetry is filled with mysticism, symbolism, and alternative perspectives on reality that challenge conventional views of the physical world.

In works like The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Jerusalem, he explores the nature of reality and the cosmos, suggesting that human understanding is limited and that true knowledge transcends the physical senses. But it’s really his poem ‘Milton’ that stood out to me which tells the story of the poet John Milton’s spirit returning to Earth to correct errors in his previous work, Paradise Lost.

“But Miltons Human Shadow continu’d journeying above The rocky masses of The Mundane Shell; in the Lands Of Edom & Aram & Moab & Midian & Amalek.

The Mundane Shell, is a vast Concave Earth: an immense Hardend shadow of all things upon our Vegetated Earth Enlarg’d into dimension & deform’d into indefinite space, In Twenty-seven Heavens and all their Hells; with Chaos And Ancient Night; & Purgatory. It is a cavernous Earth.”

William Blake ‘Milton’ (1804)

“In which is Eternity. It expands in Stars to the Mundane Shell

And there it meets Eternity again, both within and without,

And the abstract Voids between the Stars are the Satanic Wheels.

There is the Gave; the Rock; the Tree; the Lake of Udan Adan;

The Forest, and the Marsh, and the Pits of bitumen deadly:

The Rocks of solid fire: the Ice valleys: the Plains Of burning sand: the rivers, cataract & Lakes of Fire:

The Islands of the fiery Lakes: the Trees of Malice: Revenge:

And black Anxiety; and the Cities of the Salamandrine men:

(But whatever is visible to the Generated Man,

Is a Greation of mercy & love, from the Satanic Void.)

The land of darkness flamed but no light, & no repose:

The land of snows of trembling, & of iron hail incessant:

The land of earthquakes: and the land of woven labyrinths:

The land of snares & traps & wheels & pit-falls & dire mills:

The Voids, the Solids, & the land of clouds & regions of waters:

With their inhabitants: in the Twenty-seven Heavens beneath Beulah:

Self-righteousnesses conglomerating against the Divine Vision:

A Concave Earth wondrous, Chasmal, Abyssal, Incoherent!

Forming the Mundane Shell: above; beneath: on all sides surrounding

Golgonooza: Los walks round the walls night and day.”

Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion by William Blake (1804) Dante Alighieri: The Divine Comedy

Paradiso 28

The prophetic books of William Blake : Milton

https://archive.org/details/propheticbooksof00blak/page/6/mode/2up

William Blake, the Romantic Revolution, and Liberty

https://oll.libertyfund.org/publications/reading-room/2022-11-08-william-blake-the-romantic-revolution-and-liberty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Blake

Dante

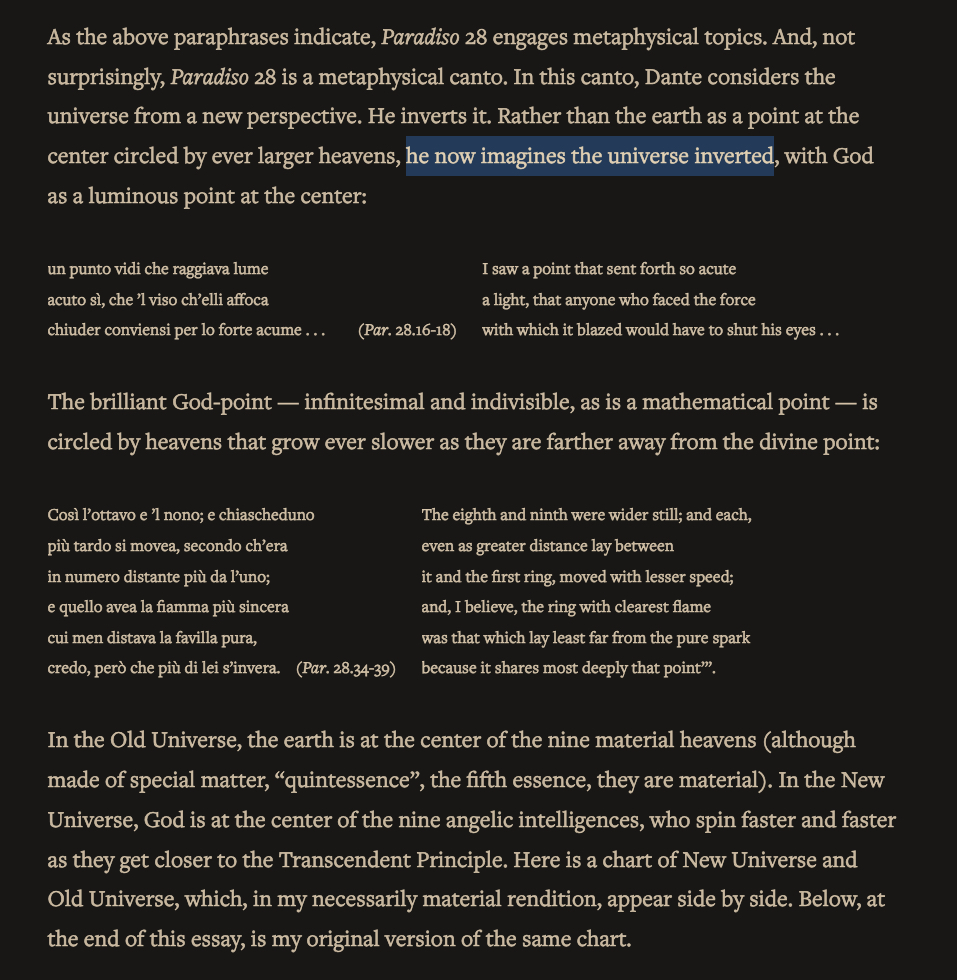

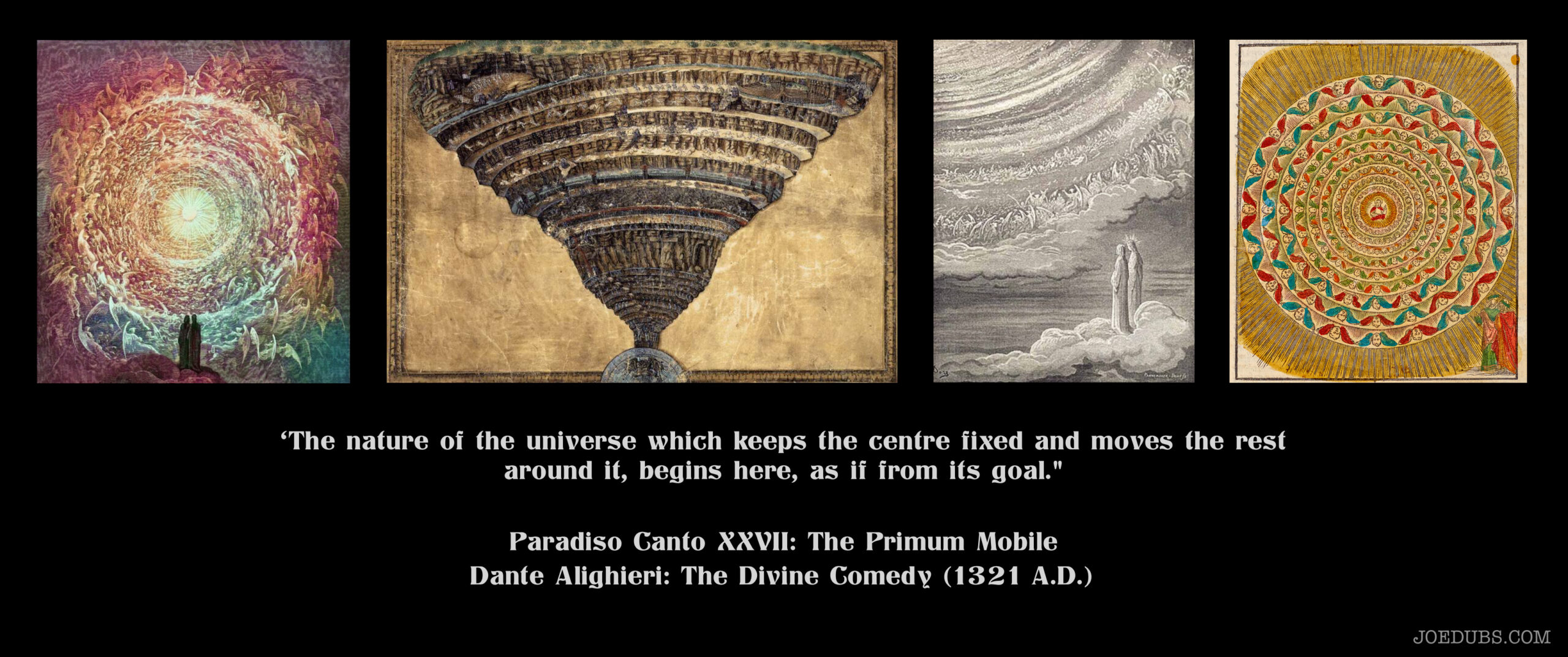

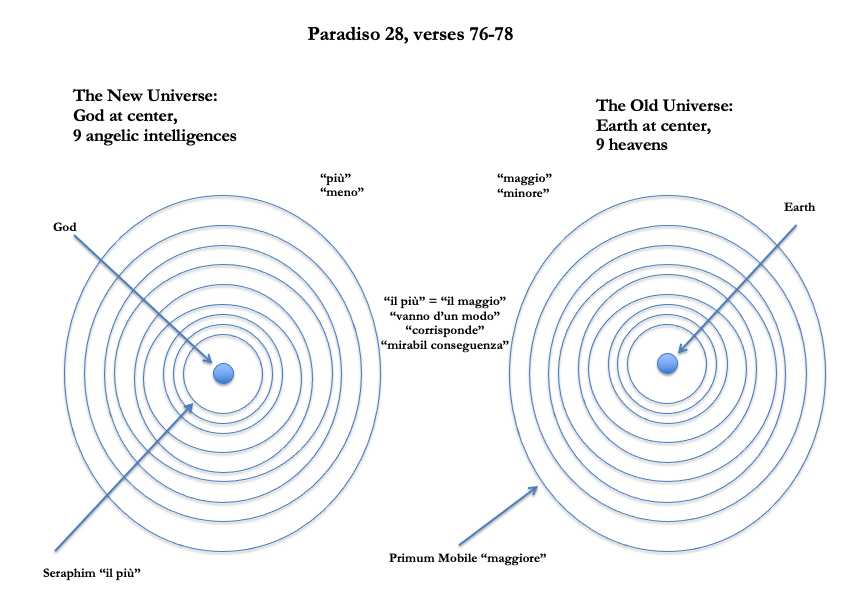

Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321 A.D.) was a renowned Italian poet, writer, and philosopher that is best known for his masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, an epic poem that takes the reader on a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. This work is considered one of the greatest literary works of all time. In it he paints a picture of nested concentric ‘heavenly spheres’ that house the planetary bodies. He explores both God and Earth as the center point of the universe.

quoting from the article: https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-28/

” In “reality”, as Dante will attempt to explain, the two universes are one. It is the attempt to explain this paradox, rather than simply affirm it, that makes Paradiso 28 one of the great intellective canti of the Paradiso.

The vision that Dante presents in Paradiso 28, where the pilgrim views God as the infinitely bright and infinitely tiny point at the center, and the various angelic intelligences as revolving circles that grow larger and slower as they grow more distant from the point, creates a visual paradox with respect to the notion of the universe we have held thus far.

By forcing us to complement the circumference model of the universe with a centrist one, Dante is trying to make us come to grips with the paradox of a point that is “enclosed by that which It encloses”: “inchiuso da quel ch’elli ’nchiude” (Par. 30.12).

This point is both center and circumference, both the deep (Augustinian) within and the great (Aristotelian) without. It is the Enclosed that Encloses/the Enclosing that is Enclosed.

This paradox is what the presentation of a second model of the universe is all about: somehow, if we can hold both New Universe and Old Universe together in our minds, we will be able to have some sense of the “unmoved mover”, of the point “that is enclosed by that which It encloses”.

“The Primum Mobile, which is the container and actualizer of all being, is itself contained by the “ciel de la divina pace”: the heaven of divine peace, the Empyrean.”

https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-28/

https://www.litcharts.com/lit/paradiso/canto-28

https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Italian/DantPar22to28.php#anchor_Toc64099985

Paradiso Canto XXVII:97-148 The Primum Mobile: Time: Degeneracy

“And the power which that look gifted me with, plucked me out of Leda’s fair nest, of the Twins, and thrust me into the swiftest Heaven. Its regions, highest and most alive, are so alike, that I cannot say in which one Beatrice chose to place me. But She, who saw my longing, began to speak, smiling, so delightedly that God seemed shining in her face: ‘The nature of the universe which keeps the centre fixed and moves the rest around it, begins here, as if from its goal.”

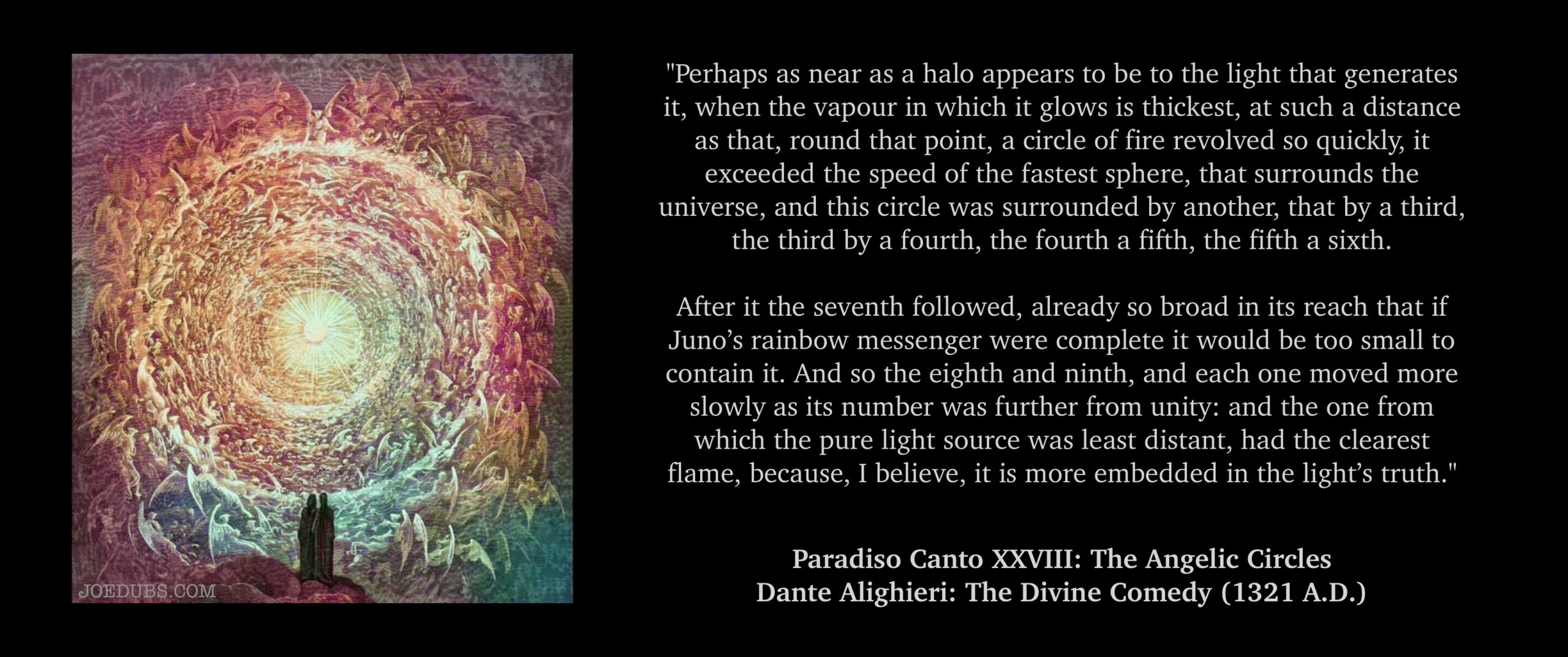

Paradiso Canto XXVIII:1-57 The Angelic Circles

“When the truth had been revealed, by her who emparadises my mind, a truth in opposition to the present life of miserable humanity, my memory recalls that, gazing on the lovely eyes, from which Love made the noose to capture me, I saw, as a candle flame lit behind a man, is seen by him in a mirror, before it is, itself, in his vision or thought, so that he turns round, to see if the glass spoke true, and sees them agreeing, as song-words to their metre: and when I turned, and my own eyes were struck by what appears in that space, whenever the eyes are correctly fixed on its orbiting, I saw a point that beamed out a light so intense, that the eye it blazes on, must be closed to its fierce brightness, and whatever star seems smallest from down here, would be a moon if it were placed alongside it, as star is placed alongside star.

Perhaps as near as a halo appears to be to the light that generates it, when the vapour in which it glows is thickest, at such a distance as that, round that point, a circle of fire revolved so quickly, it exceeded the speed of the fastest sphere, that surrounds the universe, and this circle was surrounded by another, that by a third, the third by a fourth, the fourth a fifth, the fifth a sixth.

After it the seventh followed, already so broad in its reach that if Juno’s rainbow messenger were complete it would be too small to contain it. And so the eighth and ninth, and each one moved more slowly as its number was further from unity: and the one from which the pure light source was least distant, had the clearest flame, because, I believe, it is more embedded in the light’s truth.

My Lady, who saw me labouring in profound anticipation, said; ‘Heaven and all Nature hangs from that point. Look at the circle which is most nearly joined to it, and learn that its movement is so fast because of the burning love which it is pierced by.’ And I to her: ‘If the universe was ordered in the sequence I see in these circlings, then I would be content with what I see in front of me. But, in the universe of the senses, we see the spheres as more divine the further they are distant from Earth, the centre. So, if my desire is to find its goal in this marvellous, angelic Temple, that only has love and light as its limits, I must hear why the copy and the pattern are not identical in form, since, myself, I cannot see it.’”

My Lady, who saw me labouring in profound anticipation, said; ‘Heaven and all Nature hangs from that point. Look at the circle which is most nearly joined to it, and learn that its movement is so fast because of the burning love which it is pierced by.’ And I to her: ‘If the universe was ordered in the sequence I see in these circlings, then I would be content with what I see in front of me. But, in the universe of the senses, we see the spheres as more divine the further they are distant from Earth, the centre. So, if my desire is to find its goal in this marvellous, angelic Temple, that only has love and light as its limits, I must hear why the copy and the pattern are not identical in form, since, myself, I cannot see it.’”

https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Italian/DantPar22to28.php#anchor_Toc64099985

Dante travels through the centre of the Earth in the Inferno, and comments on the resulting change in the direction of gravity in Canto XXXIV (lines 76–120)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divine_Comedy

“After drawing strength from Beatrice’s lovely gaze, Dante sees reflected in her eyes a small, single point of light with fire whirling around it. Dante counts a total of nine rings circling around the single point, each turning more slowly than the one before it. Dante is confused by this sight—to his senses, it seems that the Primum Mobile moves slowest, the outermost spheres the fastest—so Beatrice enlightens him. She explains that the size of each sphere corresponds to the diffusion of God’s power within it. So although the Primum Mobile looks like a small, slow circle from this perspective, it is actually the sphere which “most loves and knows” and speeds accordingly.

Beatrice then identifies the various angelic powers that inhabit the spheres, beginning with the Cherubim, Seraphim, and Thrones. Each of these powers, she explains, has different levels of knowledge of God (depth of sight). The next triad includes powers known as Dominations, Virtues, and Powers, and the final triad contains Principalities, Archangels, and Angels. All these powers are constantly drawn up to God, drawing all of creation up with them.” https://www.litcharts.com/lit/paradiso/canto-28

The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, 1265-1321

https://archive.org/details/divinecomedy1901dant/page/362/mode/2up

C.S. Lewis

In The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature, C.S. Lewis explores the worldview of the medieval period, focusing on the cosmology and cultural mindset that shaped the literature of the time. Dante Alighieri features prominently in this analysis because his works, particularly The Divine Comedy, epitomize the medieval synthesis of theology, philosophy, and art.

“The Medieval Model is, if we may use the word, anthropoperipheral. We are creatures of the Margin.”

“Earth is in fact the ‘offscourings of creation’, the cosmic dust-bin. This passage may also throw light on one in Milton. In Paradise Lost, VII, the Son has just marked out the spherical area of the Universe with His golden compasses”

“The spirit of this scheme, though not every detail, is strongly present in the Medieval Model. And if the reader will suspend his disbelief and exercise his imagination upon it even for a few minutes, I think he will become aware of the vast re-adjustment involved in a perceptive reading of the old poets. He will find his whole attitude to the universe inverted. In modern, that is, in evolutionary, thought Man stands at the top of a stair whose foot is lost in obscurity; in this, he stands at the bottom of a stair whose top is invisible with light.”

“The planetary Intelligences, however, make a very small part of the angelic population which inhabits, as its ‘kindly stede’, the vast aetherial region between the Moon and the Primum Mobile. Their graded species have already been described. All this time we are describing the universe spread out in space; dignity, power and speed progressively diminishing as we descend from its circumference to its centre, the Earth. But I have already hinted that the intelligible universe reverses it all; there the Earth is the rim, the outside edge where being fades away on the border of nonentity. A few astonishing lines from the Paradiso (XXVIII, 25 sq.) stamp this on the mind forever. There Dante sees God as a point of light. Seven concentric rings of light revolve about that point, and that which is smallest and nearest to it has the swiftest movement. This is the Intelligence of the Primum Mobile, superior to all the rest in love and knowledge. The universe is thus, when our minds are sufficiently freed from the senses, turned inside out. Dante, with incomparably greater power is, however, saying no more than Alanus says when he locates us and our Earth ‘outside the city wall’.

It may well be asked how, in that unfallen translunary world, there come to be such things as ‘bad’ or ‘malefical’ planets. But they are bad only in relation to us. On the psychological side this answer is implicit in Dante’s allocation of blessed souls to their various planets after death.”

(pg. 86)

“Later, in Paradise Lost, he invented a most ingenious device for retaining the old glories of the builded and finite universe yet also expressing the new consciousness of space. He enclosed his cosmos in a spherical envelope within which all could be light and order, and hung it from the floor of Heaven. Outside that he had Chaos, the ‘infinite Abyss (II, 405), the ‘unessential Night’ (438), where ‘length, breadth and highth And time and place are lost’ (891–2). He is perhaps the first writer to use the noun space in its fully modern sense—‘space may produce new worlds’ (I, 650).”

“Seven concentric rings of light revolve about that point, and that which is smallest and nearest to it has the swiftest movement. This is the Intelligence of the Primum Mobile, superior to all the rest in love and knowledge. The universe is thus, when our minds are sufficiently freed from the senses, turned inside out. Dante, with incomparably greater power is, however, saying no more than Alanus says when he locates us and our Earth ‘outside the city wall’.” (pg. 85)

“It will be seen how faithfully their triadic conception of psychological health reflects either the Greek or the later medieval idea of the nurture proper to a freeman or a knight. Reason and appetite must not be left facing one another across a no-man’s-land. A trained sentiment of honour or chivalry must provide the ‘mean’ that unites them and integrates the civilised man. But it is equally important for its cosmic implications. These were fully drawn out, centuries later, in the magnificent passage where Alanus ab Insulis compares the sum of things to a city. In the central castle, in the Empyrean, the Emperor sits enthroned. In the lower heavens live the angelic knighthood. We, on Earth, are ‘outside the city wall’. How, we ask, can the Empyrean be the centre when it is not only on, but outside, the circumference of the whole universe? Because, as Dante was to say more clearly than anyone else, the spatial order is the opposite of the spiritual, and the material cosmos mirrors, hence reverses, the reality, so that what is truly the rim seems to us the hub. (pg. 47)

must not be left facing one another across a no-man’s-land. A trained sentiment of honour or chivalry must provide the ‘mean’ that unites them and integrates the civilised man. But it is equally important for its cosmic implications. These were fully drawn out, centuries later, in the magnificent passage where Alanus ab Insulis compares the sum of things to a city. In the central castle, in the Empyrean, the Emperor sits enthroned. In the lower heavens live the angelic knighthood. We, on Earth, are ‘outside the city wall’. How, we ask, can the Empyrean be the centre when it is not only on, but outside, the circumference of the whole universe? Because, as Dante was to say more clearly than anyone else, the spatial order is the opposite of the spiritual, and the material cosmos mirrors, hence reverses, the reality, so that what is truly the rim seems to us the hub. (pg. 47)

“These facts are in themselves curiosities of mediocre interest. They become valuable only in so far as they enable us to enter more fully into the consciousness of our ancestors by realising how such a universe must have affected those who believed in it. The recipe for such realisation is not the study of books. You must go out on a starry night and walk about for half an hour trying to see the sky in terms of the old cosmology. Remember that you now have an absolute Up and Down. The Earth is really the centre, really the lowest place; movement to it from whatever direction is downward movement. As a modern, you located the stars at a great distance. For distance you must now substitute that very special, and far less abstract, sort of distance which we call height; height, which speaks immediately to our muscles and nerves. The Medieval Model is vertiginous. And the fact that the height of the stars in the medieval astronomy is very small compared with their distance in the modern, will turn out not to have the kind of importance you anticipated. For thought and imagination, ten million miles and a thousand million are much the same. Both can be conceived (that is, we can do sums with both) and neither can be imagined; and the more imagination we have the better we shall know this. The really important difference is that the medieval universe, while unimaginably large, was also unambiguously finite. And one unexpected result of this is to make the smallness of Earth more vividly felt. In our universe she is small, no doubt; but so are the galaxies, so is everything—and so what? But in theirs there was an absolute standard of comparison. The furthest sphere, Dante’s maggior corpo is, quite simply and finally, the largest object in existence. The word ‘small’ as applied to Earth thus takes on a far more absolute significance. Again, because the medieval universe is finite, it has a shape, the perfect spherical shape, containing within itself an ordered variety. Hence to look out on the night sky with modern eyes is like looking out over a sea that fades away into mist, or looking about one in a trackless forest—trees forever and no horizon. To look up at the towering medieval universe is much more like looking at a great building. The ‘space’ of modern astronomy may arouse terror, or bewilderment or vague reverie; the spheres of the old present us with an object in which the mind can rest, overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony. That is the sense in which our universe is romantic, and theirs was classical.” (pg. 73)

-The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature by C.S. Lewis (1964) (pdf book)

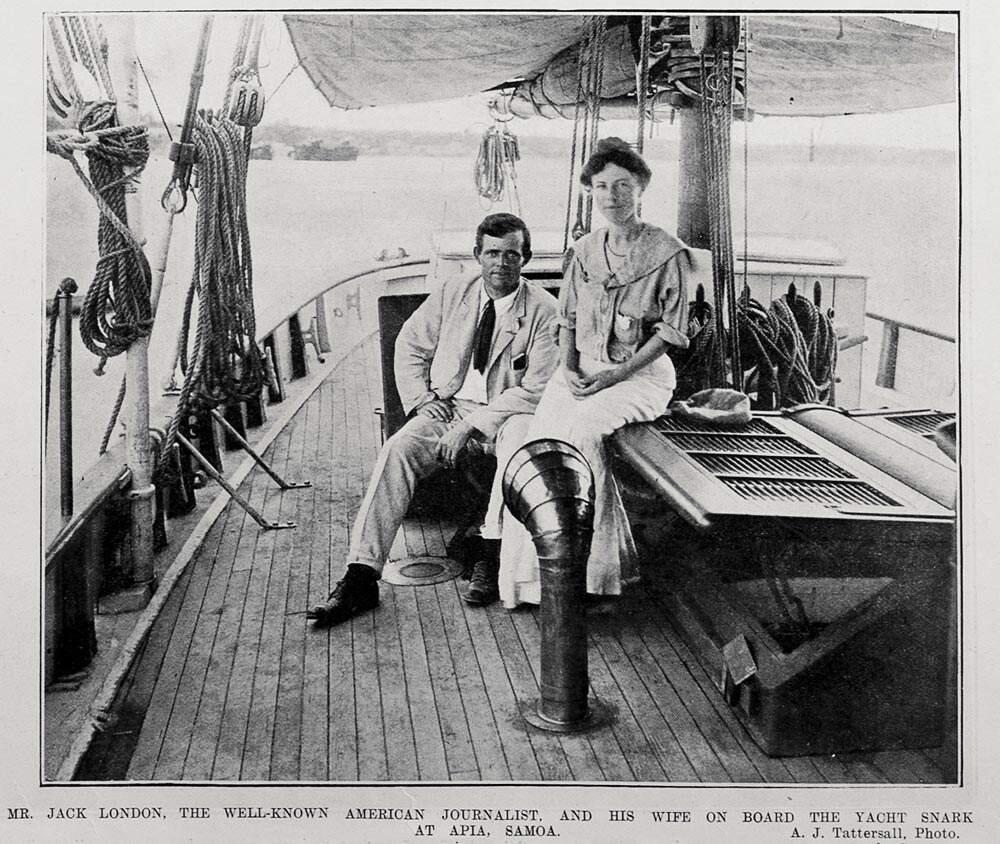

Jack London’s The Cruise of the Snark

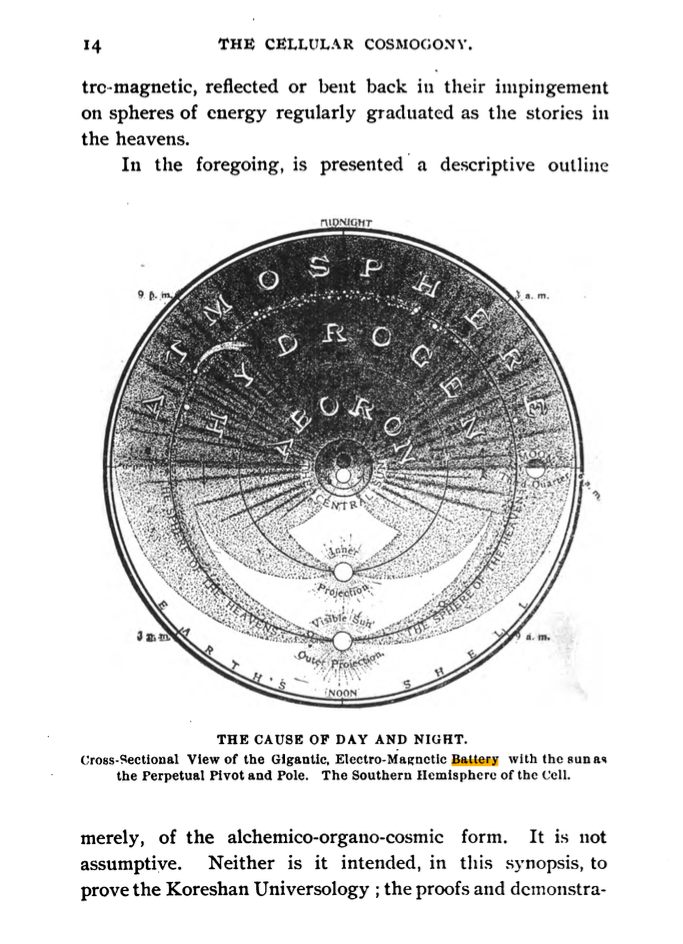

Jack London was sort of like the J.K. Rowling or Dan Brown of the early 20th century. He could afford to build a yacht, and that’s exactly what he did. He and his wife Charmian, her brother Roscoe, and a few other crew members set sail with the intention of circumnavigating the globe. Why? Well, as it happens, Roscoe was a follower of Cyrus Teed. And Jack and Roscoe would get into debates about what shape the Earth is. They both agreed that it’s spherical, however where Jack London took the traditional understanding that the water is curving down over vast distances, his fellow sailor took the exact opposite stance; earth is concave -the container for the cosmos- and we live inside our womb-Earth. The voyage was a chance to help try to settle the debate once for all.

‘London and his wife, Charmian, set sail from San Francisco aboard the Snark, a custom-built yacht, intending to circumnavigate the globe. The journey, however, was plagued by difficulties, including poor ship construction, financial troubles, crew issues, and London’s declining health.’

The Cruise of the Snark, published in 1911, was about their actual adventure around the world. As you’ll read, Charmian’s brother Roscoe, also a follower of Teed, came along for the ride and set sail for the high seas.

Jack London (1876–1916) was an American writer, journalist, and adventurer best known for his novels “The Call of the Wild” and “White Fang.”

“Despite these challenges, the book captures the thrill of exploration and his experiences in Hawaii, the Marquesas, Tahiti, Samoa, and the Solomon Islands. London describes encounters with native cultures, his fascination with surfing in Hawaii, and the hardships of long-distance sailing. Due to illness, he was forced to abandon the voyage in 1909 while in the Solomon Islands, never completing the circumnavigation.”

wikipedia

“The late Jack London and his father-in-law engaged in a heated controversy about it; so heated that they built a small sailboat, the Snark, to circumnavigate the globe and prove to one another, each that he was right.” -FIELD THEORY PUBLICITY: THE EARTH-CELL CONCEPT

(from the Sunday Item-Tribune January 5, 1936)

Chapter 1: The Cruise of the Snark

“We asserted that we were not afraid to go around the world in a

small boat, say forty feet long. We asserted furthermore that we

would like to do it. We asserted finally that there was nothing IN

this world we’d like better than a chance to do it. (^emphasis mine)

And in the meanwhile how is a fellow to find time to study

navigation–when he is divided between these problems and the

earning of the money wherewith to settle the problems? Neither

Roscoe nor I know anything about navigation, and the summer is gone,

and we are about to start, and the problems are thicker than ever,

and the treasury is stuffed with emptiness. Well, anyway, it takes

years to learn seamanship, and both of us are seamen. If we don’t

find the time, we’ll lay in the books and instruments and teach

ourselves navigation on the ocean between San Francisco and Hawaii.

There is one unfortunate and perplexing phase of the voyage of the

Snark. Roscoe, who is to be my co-navigator, is a follower of one,

Cyrus R. Teed. Now Cyrus R. Teed has a different cosmology from the

one generally accepted, and Roscoe shares his views. Wherefore

Roscoe believes that the surface of the earth is concave and that we

live on the inside of a hollow sphere. Thus, though we shall sail

on the one boat, the Snark, Roscoe will journey around the world on

the inside, while I shall journey around on the outside. But of

this, more anon. We threaten to be of the one mind before the

voyage is completed. I am confident that I shall convert him into

making the journey on the outside, while he is equally confident

that before we arrive back in San Francisco I shall be on the inside

of the earth. How he is going to get me through the crust I don’t

know, but Roscoe is ay a masterful man.

P.S.–That engine! While we’ve got it, and the dynamo, and the

storage battery, why not have an ice-machine? Ice in the tropics!

It is more necessary than bread. Here goes for the ice-machine!

Now I am plunged into chemistry, and my lips hurt, and my mind

hurts, and how am I ever to find the time to study navigation?”

So I aver, it was not Roscoe’s fault. He was like unto a god, and

he carried us in the hollow of his hand across the blank spaces on

the chart. I experienced a great respect for Roscoe; this respect

grew so profound that had he commanded, “Kneel down and worship me,”

I know that I should have flopped down on the deck and yammered.

But, one day, there came a still small thought to me that said:

“This is not a god; this is Roscoe, a mere man like myself. What he

has done, I can do. Who taught him? Himself. Go you and do

likewise–be your own teacher.” And right there Roscoe crashed, and

he was high priest of the Snark no longer. I invaded the sanctuary

and demanded the ancient tomes and magic tables,

also the prayerwheel–the sextant, I mean.

pg.50

I couldn’t help it. I tell it as a vindication of Roscoe and all

the other navigators. The poison of power was working in me. I was

not as other men–most other men; I knew what they did not know,–

the mystery of the heavens, that pointed out the way across the

deep

pg.51

CHAPTER VIII–THE HOUSE OF THE SUN

There are hosts of people who journey like restless spirits round

and about this earth in search of seascapes and landscapes and the

wonders and beauties of nature. They overrun Europe in armies; they

can be met in droves and herds in Florida and the West Indies, at

the Pyramids, and on the slopes and summits of the Canadian and

American Rockies; but in the House of the Sun they are as rare as

live and wriggling dinosaurs. Haleakala is the Hawaiian name for

“the House of the Sun.”

…Not being tourists, we of the Snark went to Haleakala. On the

slopes of that monster mountain there is a cattle ranch of some

fifty thousand acres, where we spent the night at an altitude of two

thousand feet. The next morning it was boots and saddles, and with

cow-boys and pack-horses we climbed to Ukulele, a mountain ranchhouse,

the altitude of which, fifty-five hundred feet, gives a

severely temperate climate, compelling blankets at night and a

roaring fireplace in the living-room.

There is a familiar and strange illusion experienced by all who

climb isolated mountains. The higher one climbs, the more of the

earth’s surface becomes visible, and the effect of this is that the

horizon seems up-hill from the observer. This illusion is

especially notable on Haleakala, for the old volcano rises directly

from the sea without buttresses or connecting ranges. In

consequence, as fast as we climbed up the grim slope of Haleakala,

still faster did Haleakala, ourselves, and all about us, sink down

into the centre of what appeared a profound abyss. Everywhere, far

above us, towered the horizon. The ocean sloped down from the

horizon to us. The higher we climbed, the deeper did we seem to

sink down, the farther above us shone the horizon, and the steeper

pitched the grade up to that horizontal line where sky and ocean

met. It was weird and unreal, and vagrant thoughts of Simm’s Hole

and of the volcano through which Jules Verne journeyed to the centre

of the earth flitted through one’s mind.

And then, when at last we reached the summit of that monster

mountain, which summit was like the bottom of an inverted cone

situated in the centre of an awful cosmic pit, we found that we were

at neither top nor bottom. Far above us was the heaven-towering

horizon, and far beneath us, where the top of the mountain should

have been, was a deeper deep, the great crater, the House of the

Sun. Twenty-three miles around stretched the dizzy wells of the

crater. We stood on the edge of the nearly vertical western wall,

and the floor of the crater lay nearly half a mile beneath. This

floor, broken by lava-flows and cinder-cones, was as red and fresh

and uneroded as if it were but yesterday that the fires went out.

The cinder-cones, the smallest over four hundred feet in height and

the largest over nine hundred, seemed no more than puny little

sandhills, so mighty was the magnitude of the setting. Two gaps,

thousands of feet deep, broke the rim of the crater, and through

these Ukiukiu vainly strove to drive his fleecy herds of trade-wind

clouds. As fast as they advanced through the gaps, the heat of the

crater dissipated them into thin air, and though they advanced

always, they got nowhere.

It was a scene of vast bleakness and desolation, stern, forbidding,

fascinating. We gazed down upon a place of fire and earthquake.

The tie-ribs of earth lay bare before us. It was a workshop of

nature still cluttered with the raw beginnings of world-making.

Here and there great dikes of primordial rock had thrust themselves

up from the bowels of earth, straight through the molten surface-

ferment that had evidently cooled only the other day. It was all

unreal and unbelievable. Looking upward, far above us (in reality

beneath us) floated the cloud-battle of Ukiukiu and Naulu. And

higher up the slope of the seeming abyss, above the cloud-battle, in

the air and sky, hung the islands of Lanai and Molokai. Across the

crater, to the south-east, still apparently looking upward, we saw

ascending, first, the turquoise sea, then the white surf-line of the

shore of Hawaii; above that the belt of trade-clouds, and next,

eighty miles away, rearing their stupendous hulks out of the azure

sky, tipped with snow, wreathed with cloud, trembling like a mirage,

the peaks of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa hung poised on the wall of

heaven. pg.109

There was no way by which the great world could intrude. Our bell

rang the hours, but no caller ever rang it. There were no guests to

dinner, no telegrams, no insistent telephone jangles invading our

privacy. We had no engagements to keep, no trains to catch, and

there were no morning newspapers over which to waste time in

learning what was happening to our fifteen hundred million other

fellow-creatures.

But it was not dull. The affairs of our little world had to be

regulated, and, unlike the great world, our world had to be steered

in its journey through space. Also, there were cosmic disturbances

to be encountered and baffled, such as do not afflict the big earth

in its frictionless orbit through the windless void. And we never

knew, from moment to moment, what was going to happen next. There

were spice and variety enough and to spare. Thus, at four in the

morning, I relieve Hermann at the wheel. pg.126

Just as the compass is tricky and strives to fool the mariner by

pointing in all directions except north, so does that guide post of

the sky, the sun, persist in not being where it ought to be at a

given time. This carelessness of the sun is the cause of more

trouble–at least it caused trouble for me. To find out where one

is on the earth’s surface, he must know, at precisely the same time,

where the sun is in the heavens. That is to say, the sun, which is

the timekeeper for men, doesn’t run on time. When I discovered

this, I fell into deep gloom and all the Cosmos was filled with

doubt. Immutable laws, such as gravitation and the conservation of

energy, became wobbly, and I was prepared to witness their violation

at any moment and to remain unastonished. For see, if the compass

lied and the sun did not keep its engagements, why should not

objects lose their mutual attraction and why should not a few bushel

baskets of force be annihilated? Even perpetual motion became

possible, and I was in a frame of mind prone to purchase Keeley Motor

stock from the first enterprising agent that landed on the

Snark’s deck. And when I discovered that the earth really rotated

on its axis 366 times a year, while there were only 365 sunrises and

sunsets, I was ready to doubt my own identity.

This is the way of the sun. It is so irregular that it is

impossible for man to devise a clock that will keep the sun’s time.

The sun accelerates and retards as no clock could be made to

accelerate and retard. The sun is sometimes ahead of its schedule;

at other times it is lagging behind; and at still other times it is

breaking the speed limit in order to overtake itself, or, rather, to

catch up with where it ought to be in the sky. In this last case it

does not slow down quick enough, and, as a result, goes dashing

ahead of where it ought to be. In fact, only four days in a year do

the sun and the place where the sun ought to be happen to coincide.

The remaining 361 days the sun is pothering around all over the

shop. Man, being more perfect than the sun, makes a clock that

keeps regular time. Also, he calculates how far the sun is ahead of

its schedule or behind. The difference between the sun’s position

and the position where the sun ought to be if it were a decent,

self-respecting sun, man calls the Equation of Time. Thus, the

navigator endeavouring to find his ship’s position on the sea, looks

in his chronometer to see where precisely the sun ought to be

according to the Greenwich custodian of the sun. Then to that

location he applies the Equation of Time and finds out where the sun

ought to be and isn’t. This latter location, along with several

other locations, enables him to find out what the man from Kansas

demanded to know some years ago. pg.216

Edgar Allen Poe – https://joedubs.com/high-altitude-observations-of-earth/

Discover more from JoeDubs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.