:by Sharyl Attkisson

Consider this fictitious example that’s inspired by real life: say you’re watching the news, and you see a story about a new study on the cholesterol-lowering drug called cholextra. The study says cholextra is so effective that doctors should consider prescribing it to adults and even children who don’t yet have high cholesterol.

Is it too good to be true? You’re smart, you decide to do some of your own research. You do a Google search, you consult social media, Facebook, and Twitter. You look at Wikipedia, WebMD, a non-profit website, and you read the original study in a peer-reviewed published medical journal. It all confirms how effective cholextra is. You do run across a few negative comments and a potential link to cancer, but you dismiss that, because medical experts call the cancer link a myth and say that those who think there is a link, they are quacks, cranks, and nuts.

Finally, you learn that your own doctor recently attended a medical seminar. The lecture that he attended confirmed how effective cholextra is, so he sends you off with some free samples and a prescription. You’ve really done your homework.

But what if all isn’t as it seems? What if the reality you found was false; a carefully-constructed narrative by unseen special interests designed to manipulate your opinion? A Truman Show-esque alternate reality all around you? Complacency in the news media combined with incredibly powerful propaganda and publicity forces mean we sometimes get little of the truth. Special interests have unlimited time and money to figure out new ways to spin us while cloaking their role.

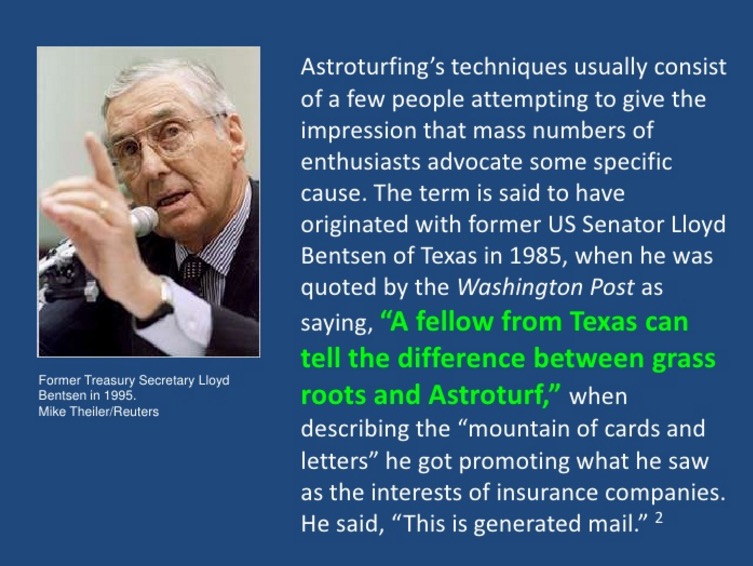

Surreptitious astroturf methods are now more important to these interests than traditional lobbying of Congress. There’s an entire industry built around it in Washington.

What is an astroturf?

It’s a perversion of grassroots, as in fake grassroots. Astroturf is when political, corporate, or other special interests disguise themselves and publish blogs, start Facebook and Twitter accounts, publish ads and letters to the editor, or simply post comments online to try to fool you into thinking an independent or grassroots movement is speaking. The whole point of astroturf is to try to get the impression there’s widespread support for or against an agenda when there’s not.

Astroturf seeks to manipulate you into changing your opinion by making you feel as if you’re an outlier when you’re not. One example is the Washington Redskins’ name. Without taking a position on the controversy, if you simply were looking at news media coverage over the course of the past year, or looking at social media, you probably have to conclude that most Americans find that name offensive and think it ought to be changed.

But what if I told you 71% of Americans say the name should not be changed? That’s more than two-thirds. Astroturfers seek to controversialize those who disagree with them. They attack news organizations that publish stories they don’t like, whistleblowers who tell the truth, politicians who dare to ask the tough questions, and journalists who have the audacity to report on all of it.

Sometimes, astroturfers simply shove intentionally so much confusing and conflicting information into the mix that you’re left to throw up your hands and disregard all of it, including the truth; Drown out a link between a medicine and a harmful side effect say, vaccines and autism, by throwing a bunch of conflicting paid-for studies, surveys, and experts into the mix, confusing the truth beyond recognition.

And then, there’s Wikipedia; astroturf’s dream come true

Built as the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit, the reality can’t be more different. Anonymous Wikipedia editors control and co-opt pages on behalf of special interests. They forbid and reverse edits that go against their agenda. They skew and delete information in blatant violation of Wikipedia’s own established policies with impunity. Always superior to the poor schlubs who actually believe anyone can edit Wikipedia only to discover they’re barred from correcting even the simplest factual inaccuracies.

Try adding a footnoted fact or correcting a fact error on one of these monitored Wikipedia pages, and poof! sometimes within a matter of seconds you’ll find your edit is reversed. In 2012, famed author Philip Roth tried to correct a major fact error about the inspiration behind one of his book characters cited on a Wikipedia page, but no matter how hard he tried, Wikipedia’s editors wouldn’t allow it. They kept reverting the edits back to the false information.

When Roth finally reached a person at Wikipedia – which was no easy task – and tried to find out what was going wrong, they told him he simply was not considered a credible source on himself.

A few weeks later, there was a huge scandal when Wikipedia officials got caught offering a PR service that skewed and edited information on behalf of paid publicity-seeking clients, in utter opposition to Wikipedia’s supposed policies. All of this may be why, when a medical study looked at medical conditions described on Wikipedia pages and compared it to actual peer-reviewed published research, Wikipedia contradicted medical research 90% of the time. You may never fully trust what you read on Wikipedia again, nor should you.

Let’s now go back to that fictitious cholextra example and all the research you did. It turns out the Facebook and Twitter accounts you found that were so positive, were actually written by paid professionals hired by the drug company to promote the drug. The Wikipedia page had been monitored by an agenda editor, also paid by the drug company.

The drug company also arranged to optimize Google search engine results so it was no accident that you stumbled across that positive non-profit that had all those positive comments. The non-profit was, of course, secretly founded and funded by the drug company. The drug company also financed that positive study and used its power of editorial control to omit any mention of cancer as a possible side-effect.

Once more, each and every doctor who publicly touted cholextra or called the cancer link a myth, or ridiculed critics as paranoid cranks and quacks, or served on the government advisory board that approved the drug, each of those doctors is actually a paid consultant for the drug company.

As for your own doctor, the medical lecture he attended that had all those positive evaluations was in fact, like many continuing medical education classes, sponsored by the drug company. And when the news reported on that positive study, it didn’t mention any of that. I have tons of personal examples from real life.

A couple of years ago, CBS News asked me to look into a story about a study coming out from the non-profit National Sleep Foundation. Supposedly, this press release coming out said the study concluded we are a nation with an epidemic of sleeplessness, and we don’t even know it, and we should all go ask our doctors about it.

A couple of things struck me about that. First, I recognized the phrase “ask your doctor” as a catch phrase promoted by the pharmaceutical industry. They know that if they can get your foot through the door at the doctor’s office to mention a malady, you’re very likely to be prescribed the latest drug that’s marketed.

Second, I wondered how serious an epidemic of sleeplessness could really be if we don’t even know that we have it. It didn’t take long for me to do a little research and discover that the National Sleep Foundation non-profit, and the study which was actually a survey not a study, were sponsored in part by a new drug that was about to be launched onto the market, called Lunesta, a sleeping pill.

I reported the study, as CBS News asked, but of course, I disclosed the sponsorship behind the non-profit and the survey so the viewers could weigh the information accordingly. All the other news media reported the same survey directly off the press release, as written, without digging past the superficial. It later became an example written up in the Columbia Journalism Review, which quite accurately reported that only we, at CBS News, had bothered to do a little bit of research and disclose the conflict of interest behind this widely reported survey.

So now you may be thinking, “What can I do? I thought I’d done my research. What chance do I have separating fact from fiction, especially if seasoned journalists with years of experience can be so easily fooled?”

I have a few strategies that I can tell you about to help you recognize signs of propaganda and astroturf. Once you start to know what to look for, you’ll begin to recognize it everywhere.

First, hallmarks of astroturf include use of inflammatory language such as “crank”, “quack”, “nutty”, “lies,” “paranoid”, “pseudo”, and “conspiracy”. Astroturfers often claim to debunk myths that aren’t myths at all. Use of the charged language test well: people hear something’s a myth, maybe they find it on Snopes, and they instantly declare themselves too smart to fall for it.

But what if the whole notion of the myth is itself a myth, and you and Snopes fell for that? Be aware when interests attack an issue by controversializing or attacking the people, personalities, and organizations surrounding it rather than addressing the facts. That could be astroturf.

And most of all, astroturfers tend to reserve all of their public skepticism for those exposing wrongdoing rather than the wrongdoers. In other words, instead of questioning authority, they question those who question authority. You might start to see things a little more clearly; it’s like taking off your glasses, wiping them, and putting them back on, realizing, for the first time, how foggy they’d been all along.

I can’t resolve these issues, but I hope that I’ve given you some information that will at least motivate you to take off your glasses and wipe them, and become a wiser consumer of information in an increasingly artificial, paid-for reality.

Thank you.

-Sharyl Attkisson

Video: Astroturf and manipulation of media messages | Sharyl Attkisson | TEDxUniversityofNevada